🌿 A conversation with Katie, the Orin & Charlette Gelderloos Environmental Leadership Intern, and ghost stream expert, Dr. Jacob Napieralski🌿

Katie: You’ve said, “the landscape remembers” in terms of ghost streams and their displacement in favor of urban development. How can knowing about these historical features inform future flood planning by agencies or organizations?

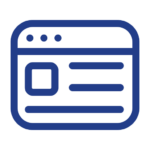

Jacob: Landscape literacy, or the ability to understand the origins and importance of natural landforms, can inform how best to engineer the landscape for growing populations. Rivers and wetlands are perfect examples – civilizations started along the banks of rivers, but the industrial revolution accelerated human dislike for bodies of water that were not fully appreciated for their ecosystem services. Thus, we removed them. But now, many cities are filled with these ghost channels and wetlands. There are neighborhoods that are not at risk from a river overflowing its river banks, but still flood, and the reason may be because the landscape still slopes towards a ghost channel. Knowing where these ghost channels are can lead to better informed decisions about managing flood risks.

Katie: What do you hope happens with these ghost streams?

Jacob: So what to do about ghost streams? Here are three recommendations: (1) It is important to stop the burial of waterbodies in new development and agricultural projects and instead integrate waterbodies into development plans. (2) There is no comprehensive mapping plan, nor database, that shows the presence of ghost channels and wetlands. This is valuable data that should be accessible to residents, urban planners, and water authorities. (3) Ghost streams increase flood risk, so if we know where they are, we can mitigate or adapt to the problem. While stream daylighting is seen as an option, they can be expensive and difficult to integrate into complex landscapes. Rather, it is important to inform residents of the risk of living on a ghost channel or to provide ways to manage excess water during heavy rain events. Additionally, simple green infrastructure projects, like rain gardens, can be placed in these depressions in the landscape to slow down and capture runoff instead of overwhelming homes and stormwater systems.

Katie: A new generation of environmental professionals is emerging. How can they tackle issues like these?

Jacob: They require a new generation of problem solvers that can think outside of the box (or as if there is no box!), understand how to involve as many stakeholders as possible in the decision making process, and approach the problem from an interdisciplinary lens. It is important to not necessarily “fix it for now” but rather develop long term goals that see our partnership with nature nurtured in a sustainable way for all community members. This means the next generation of environmental scientists should be broadly trained, resilient, and savvy.

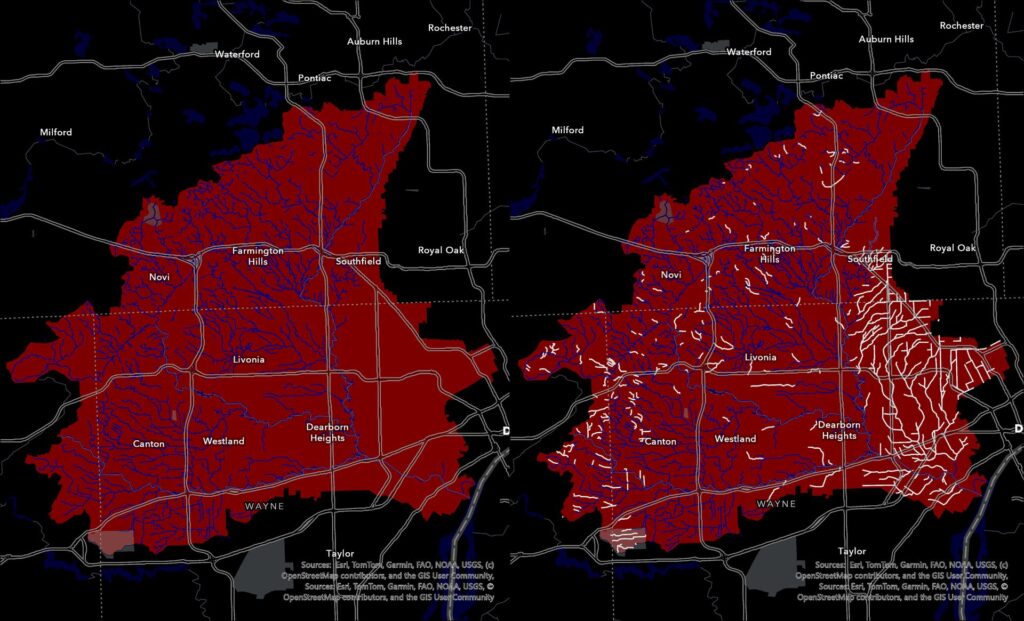

images above – (left) the Rouge River system highlighted in blue set in the entirety of the Rouge River Watershed in red; (right) similar image as left with “Ghost” streams, or the buried parts of the Rouge River system, highlighted in white.

Categories

-

BlogRead the latest blog posts from your FOTR team.

BlogRead the latest blog posts from your FOTR team.