GET TO KNOW

Birds in Winter

Winter landscapes have a beauty all their own, and winter birdwatching hikes are a wonderful way to see our feathered friends. Yet, if one is a cold weather “couch potato,” one may prefer to check recent bird sightings on a site called eBird, where dedicated birdwatchers record and share sightings of birds large and small. One example comes from the campus of the University of Michigan-Dearborn.

FUN FACT: Around the country, and around the world, dedicated bird-watchers staff official bird observatory stations and log reams of year-round data. Much of this data is uploaded to Cornell University’s eBird website, where the information is available to both amateur bird lovers and researchers who study bird populations, migrations, and distributions.

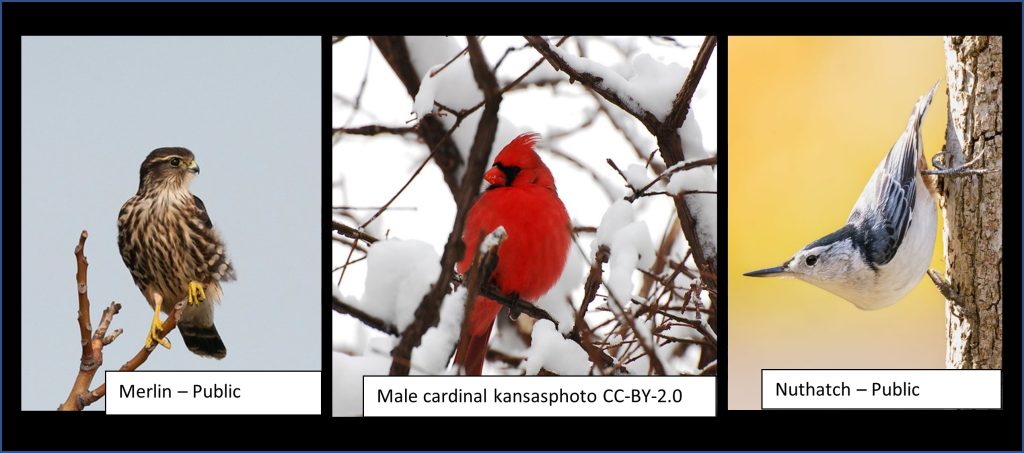

A perusal of sightings from January 12th reveals a handful of backyard regulars (a robin, sparrow, starling, and cardinal), one raptor (a Merlin) and a collection of small, insectivorous birds such as chickadees and nuthatches. All in all, it was an interesting combination of sightings for a single day.

THE RAPTOR

For those intrigued by raptors, the Merlin sighting may be of special interest. Merlins (Falco columbarius) are small falcons that are similar in size to Blue Jays. Back in the 1960s-1970s, when DDT spraying was a widespread practice, Merlin populations declined severely. Today populations have increased and are considered stable, but individual Merlin sightings remain relatively uncommon.

There are three sub-species of Merlins found in North America. The taiga subspecies is the most widespread and the one most likely to be found in Michigan. Taiga Merlins are migratory, and most individuals spend the winter in the south. Yet, with overall global warming trends – and sufficiently available prey – some individual birds may delay, or even forego migration.

Taiga males display a pattern of grayish wings with mottled brown/white chest feathers while females and young birds have lighter brown wings. Like all falcons, Merlins are strong and swift fliers. However, unlike their well-known Peregrine cousins, Merlins do not engage in high-speed nosedives to capture prey. Instead, Merlins perch, flush, and capture prey (such as small birds and dragonflies) in level flight. And while most raptors are solitary hunters, Merlins are known to hunt cooperatively. One individual Merlin may serve as flusher while hunting partners chase down startled prey.

THE PREY FLOCK

Another interesting feature from the January 12th bird sightings is the combination of chickadees, nuthatches and small woodpeckers – plus a Carolina Wren and a Brown Creeper. At first glance, this combination may appear random and unrelated, but there is a very good chance these small birds were members of a “mixed flock.”

In contrast to large single-species flocks (think thousands of starlings on a wire or gatherings of pretty pink flamingos), mixed flocks have well-documented patterns in which unrelated bird species join together for foraging. Such mixed flocks are informal and transitory, and often include only a smallish number of birds. A self-appointed leader – who is a member of the most dominant species present – will somehow rally the group, and the others follow along.

The sighted combination of chickadees, nuthatches, small woodpeckers, Carolina Wren, and Brown Creeper is a typical group in this region. This group is frequently accompanied by titmice and kinglets. Titmice and kinglets are also small insectivorous birds, and some may have been present – but unseen – on that day. Note that kinglets, especially, are very tiny birds that are only about the size of hummingbirds.

Within this type of mixed flock, a chickadee (or titmouse, if present) would typically serve as lead bird. Researchers believe individual participants in mixed flocks may gain some overall, synergistic advantage for foraging. Each individual species has different skill sets for finding potential food sites and for spotting predators. However, if the various species employ non-competing foraging techniques, everyone in the group remains a bit safer without getting in each other’s way. Of course, there is a measure of safety in numbers, but there is no doubt that – on January 12th – the nearby Merlin was very well-aware of that small flock of tiny birds.

THE BACKYARD STANDARDS

As year-round Michigan inhabitants, starlings, cardinals, and many sparrows are always happy to supplement scarce winter food supplies with offerings from bird feeders.

Though non-native and considered a nuisance species that damages crops and out-competes other native cavity nesters like bluebirds, starlings are interesting birds. They feed primarily on insects during summer months, but happily switch to fruits and seeds for winter. While they appear plain black from a distance, up close they are actually attractive. They have unique feathers that are spotted during winter but fade to an iridescent sheen in summer. Intentionally imported from Europe in the late 1800’s, these birds are now the one of the most common birds found across North America.

Breeding pairs of Northern Cardinals are openly affectionate, and their frequent, joint visits to the bird feeder are a joy to watch. Based on personal observations of the author, it appears that the male cardinal often appears first to scout for danger and then stands guard while his lady dines.

With more than twenty different types of sparrows that call Michigan home for at least part of the year, the general term sparrow can refer to a great many birds. Two of the most common species that sport the stereotypical sparrow look (small, nondescript, brownish bird) are Song Sparrow and White-throated Sparrows.

Song sparrows and white-throated sparrows are both small, ground foraging birds that eat a mixture of insects (when available), fruits, seeds and berries. Overall, both species prefer to stay hidden among branches and tall grasses. However, male song sparrows earn the species’ name by venturing out on branch tips to sing for the females. Between these two sparrow breeds, song sparrows are slightly smaller with varying patterns of striping on the breast. The slightly larger white-throated sparrows can usually be identified by a distinctive yellow patch above the eyes.

Robins are traditionally considered a migratory species that moves about in great, single-species flocks. Nonetheless, these birds are able (and apparently willing) to survive winter’s cold weather if there are sufficient food supplies. Everyone knows that robins love dining on worms. They eat fruit in winter and invertebrates when there is no cover, and can be largely nomadic in search of fruit. They may appear at feeders and eat suet or rarely a peanut or sunflower seed, but only in a pinch.

TAKE ACTION

Worldwide, bird populations are declining due to overall habitat loss and widespread use of pesticides, herbicides, and other toxic chemicals. Insect populations are also declining for the same reasons, and since many birds are insectivores, declines in insect populations further harm bird populations. Additionally, birds often suffer from collisions with glass buildings and home windows, and from the disorienting effects of light pollution across migratory flyways.

There are many ways to help our feathered friends. In addition to planting appropriate native trees, shrubs, flowers, and grasses, it is important to refrain from spraying lawn chemicals. Additionally, grid patterns may be purchased and adhered to windows to reduce window collisions, and everyone can reduce the use of excessive outdoor lighting.

Overall, birds are some of the most beautiful creatures on earth, and our lives would be greatly diminished without them. Let us protect them while we still can.

Categories

-

News & EventsLearn more about upcoming FOTR events and projects